The Anticipation is Worth More than the Reward.

A cartoon illustrating a bottle of dopamine cheering on a human called Barry.

It is no secret that humans are prone to addiction. A behavior that causes us to repetitively return to an activity, application or interaction. At the core of it is a reward, something that we believe we are getting out of it.

For smoking, it’s the reduction in stress or the time out. For football, it’s the sense of victory and collective. For research its the knowledge or findings that come from it. For Instagram, it’s the follower, like or comment that may arise. For gambling, its the monetary gain that arises from the event at hand.

It’s this reward that releases dopamine and gives us a sense of pleasure, achievement and gain. A feeling that gets us hooked to the experience. However, what I did not expect to discover is that it is not the reward itself that gives us this feeling, but instead — the anticipation of getting this reward. That magical feeling of uncertainty that leaves you thrilled, wondering if you will get your treasure. That’s what gets you hooked.

What’s even more interesting is that the more variable that this reward is, the more hooked you get to an activity. Here’s the research.

The Nucleus Accumbens is the Brain’s Pleasure Center

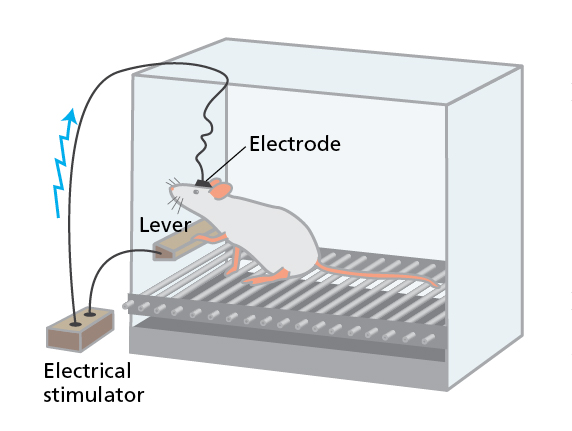

This discovery began in the 1940s by James Olds and Peter Milner, whom implanted electrodes in the brains of lab mice that enabled the mice to give themselves tiny electric shocks to a small area of the brain known as the nucleus accumbens. The mice quickly became addicted to triggering the shock and would even forgo food, water and even run across painful electrified grids for the opportunity to receive the treatment.

A couple of years later, other researchers tested the human response to self-administered stimuli in the nucleus accumbens. The results where just as tramatic as those with the mice — subjects did not want to do anything but press the button. In fact, it was so addictive that researchers had to forcibly take the devices away from subjects.

These results motivated the science community to believe that they had discovered the brains pleasure center.

It’s not the reward, it’s the anticipation.

In 2008, Stanford Professor Brian Knutson conducted a study that explored how a humans blood would circulate in the brain as they gambled. As the experiment was carried out, Knutson and his fellows would analyze which areas of the brain became more active.

The results of this experiment were startling and showed that the nucleus accumbens was not activating when the reward was received but rather in anticipation of it. A finding that led the researchers to suggest “that what draws us to act is not the sensation we receive from the reward itself but the need to alleviate the craving for that reward.”

Variable rewards raise the prize.

In 1950, Psychologist B.F Skinner conducted an experiment to understand how variability impacted animal behavior. Skinner placed pigeons inside a box rigged to deliver a food pellet to the birds every time they pressed a lever. Similar to Olds and Milner, the pigeons learned the cause and effect relationship between pressing the lever and receiving the food.

In the next part of the experiment, Skinner added variability by changing the number of taps required to make the discharge food. This experiment revealed that the intermittent reward dramatically increased the number of times the pigeons tapped the lever.

More recent experiments revel that variability increases activity in the nucleus accumbens and spikes levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, driving our hungry search for rewards. Findings that demonstrate that variable rewards will push products to be more addictive.